This small exhibition presents a selection of books about exploring, trekking and travelling in Central Asia. The selection is intended to illustrate the published form of books from three distinct periods: the 1880s & 90s, when the ‘Great Game’, played out between the competing empires of Britain, Russia and China, was nearing its apogee; the 1930s, when the exploits of explorers, archaeologists and ethnographers were giving way to those of writer-adventurers; and the 1990s & 2000s, when travellers rediscovered the newly independent post-Soviet Central Asian republics and reported on their efforts to forge new national identities.

Throughout these years, the physical form of the books inevitably changes, from heavyweight tome to lightweight paperback. But certain features are integral and unchanging: cartographic maps of often considerable sophistication; photographic documentation of epic landscapes, picturesque caravans and weathered travellers; and no-nonsense writing that describes with often amusing consistency the character of the indigenous peoples. Reading these books now provides a view into the idiosyncrasies of this sphere of publishing, some understanding of the varied and yet persistent qualities of travel writing about this region, and historical insights (of a kind) into more recent or now current events playing out in Afghanistan, Kashmir, western China and elsewhere in Central Asia.

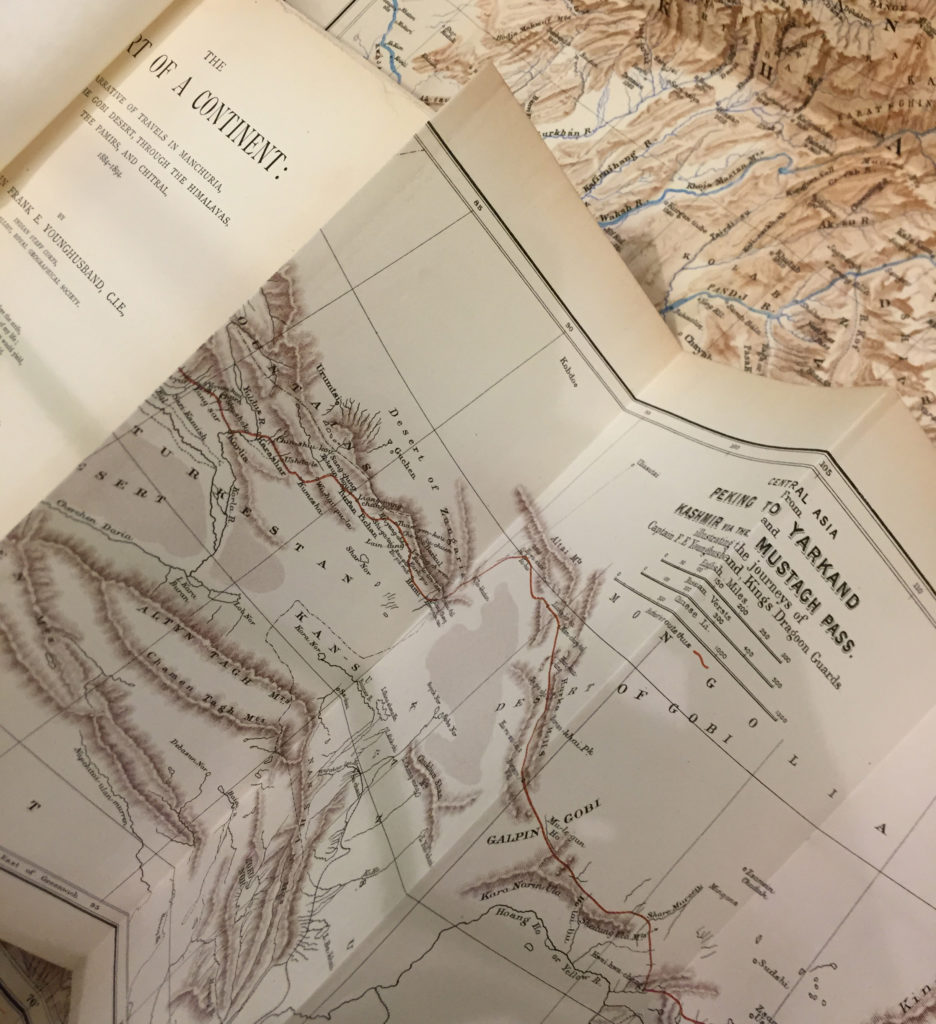

Capt Frank E. Younghusband

The heart of a continent (1896)

Captain Frank E. Younghusband (later Sir Francis, 1863–1942) has been described by his biographer as the ‘last great imperial adventurer’. Early in his career in the British army in India, he was captivated by treks he made in Kashmir and elsewhere in the frontier region of northwest India. He soon convinced his superiors to let him travel more extensively in northeast China (Manchuria) and thereafter from Peking (Beijing) across the Gobi desert to the far west of China (Xinjiang), over the Karakoram range of mountains (near K2), eventually arriving back in Kashmir.

These and subsequent journeys made over a period of ten years (1884–1894), including in the Pamirs (modern day Tajikistan), the Hindu Kush (Afghanistan) and Chitral (now northern Pakistan), make up the narrative of The heart of a continent. Although Younghusband was serving in an intelligence-gathering role for the British, and sometimes as a ‘correspondent’ for The Times of London, the detailed journals he kept and the numerous photographs that were taken provided the material for this popular account of his adventures, which sold very well (four editions in its first year of publication) to a British public hungry for tales of hardship and derring-do in these remote, rugged and contested areas.

Not unlike the heavily-equipped caravans that made up some of the expeditions led by Younghusband, The heart of a continent is a hefty volume of 400+ pages. It is extensively illustrated with halftone photographs, woodcuts derived from photographs, and drawn and painted renditions of photographic scenes made by artists working in Britain. Fold-out maps are conspicuous: the book has four, covering the regions travelled through. Three are ‘tipped in’ and the fourth is held in a pocket at the back; each allow the armchair explorer back home to follow Younghusband’s routes. They are perhaps an indication of the importance given to mapping and surveying during these journeys. The work was done for the British government (and military), while bodies such as the Royal Geographical Society took a close interest in Younghusband’s activities. During this time the RGS elected him its youngest member and awarded him its Gold Medal.

Younghusband was reflective by nature and in his ‘impressions of travel’, the final chapter in The heart of a continent, he considers the place of humans amidst the grandeur of earth and the universe. His musings were a prelude to the religious mysticism and intense spirituality he would later explore in many books published after his trekking days were over.

Captain Frank E. Younghusband, The heart of a continent: a narrative of travels in Manchuria, across the Gobi desert, through the Himalayas, the Pamirs, and Chitral, 1884–1894

Third edition, London: John Murray, 1896, 402 pp. + prelims and index. With numerous drawings, photographs (halftone), woodcut illustrations (from photographs) and four maps.

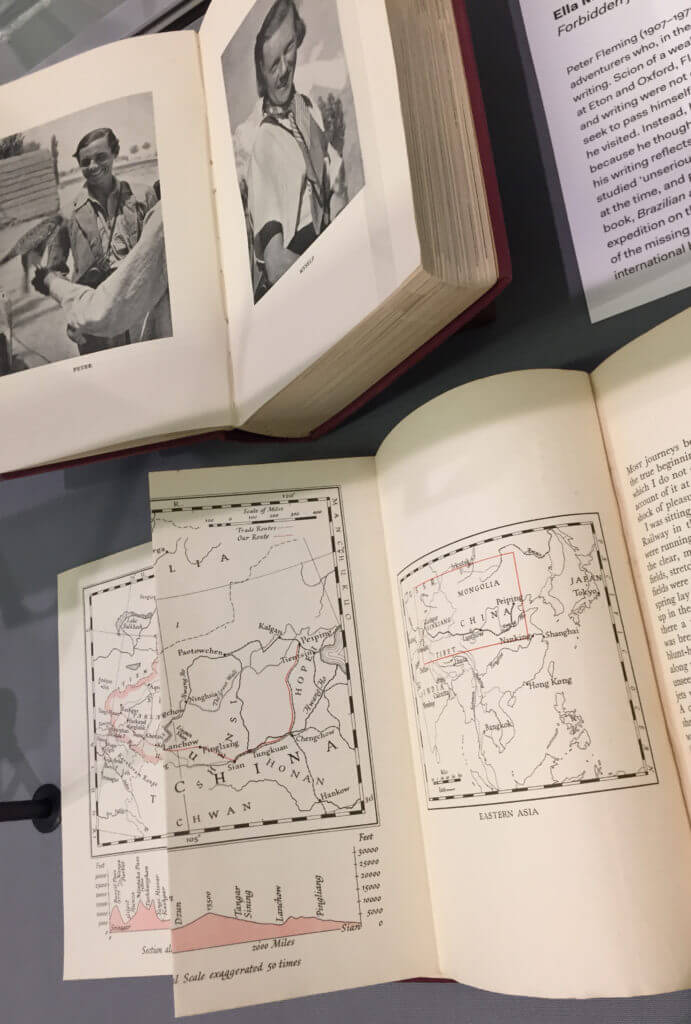

Peter Fleming

News from Tartary (1936)

Ella Maillart

Forbidden journey (1937)

Peter Fleming (1907–1971) was among a group of writer-adventurers who, in the 1930s, helped refresh travel writing. Scion of a wealthy banking family, educated at Eton and Oxford, Fleming’s ambitions for travelling and writing were not grand or scholarly, nor did he seek to pass himself off as an expert of the regions he visited. Instead, he sought out adventure above all because he thought it would be a pleasure and fun, and his writing reflects this. His attractive style conveys a studied unseriousness that proved new and different at the time, and popular among readers. His first travel book, Brazilian adventure (1933), narrating a plucky expedition on the Araguaia and Tapirapé rivers in search of the missing explorer Colonel Percy Fawcett, was an international bestseller.

In 1934, Fleming embarked on his third trip to the Far East, travelling along the Trans-Siberian Railway. He was on assignment for The Times of London to report on developments in Manchukuo (Japanese-occupied Manchuria) and elsewhere. While there, he met up with Ella Maillart (1903–1997), a Swiss writer-adventurer who was among the first (western) women to travel solo in Central Asia. In early 1935 they effected a grudging agreement to undertake a journey together – by train and truck, but mostly by horse and camel caravan – from Peking (Beijing) to India via China’s ancient captial Xi’an, through northern Tibet, along the southern edge of the Taklamakan desert to Kashgar (Xinjiang), into the Pamirs and over the Mintaka Pass, to Srinagar in Kashmir. They joked about the prospects of travelling as a pair, noting ominously the titles of their most recent books: One’s company (Fleming) and Turkistan solo (Maillart).

Each wrote a book about their shared journey, Fleming’s titled News from Tartary (1936) and Maillart’s Oases interdites / Forbidden journey (1937). Both books follow a familiar pattern in their published form: maps near the start and photographs throughout, complementing the text. Together, the maps, photographs and texts convey the hardships and revelations of travel, the lives of people met along the way, and impressions of the little known and often harsh regions visited. Fleming and Maillart took their own photographs using Leica compact cameras. Both proved accomplished photographers; judging from their shots of each other, they appear to have carried their cameras almost constantly. Travel conditions and caravan mishaps regularly threatened their stocks of exposed and unexposed film.

While Fleming and Maillart would travel (and write) extensively throughout their lives, their epic and colourful journey together is the one for which they are perhaps best remembered. Fleming settled soon after on the family estate at Nettlebed, near Henley-on-Thames, and in his later years became a member of Council at the University of Reading, which also holds some of his papers. Maillart lived alone to a great age in Switzerland, celebrated as a pioneer among women travellers.

Peter Fleming, News from Tartary: a journey from Peking to Kashmir

First edition, London: Jonathan Cape, 1936, 381 pp. + prelims and index.

With numerous photographs (by the author) and two maps (courtesy of the Royal Geographical Society).

Ella Maillart, Forbidden journey: from Peking to Kashmir

First edition, London: William Heinemann, 1937, 301 pp. + prelims, notes and index. With numerous photographs (by the author) and three maps (uncredited).

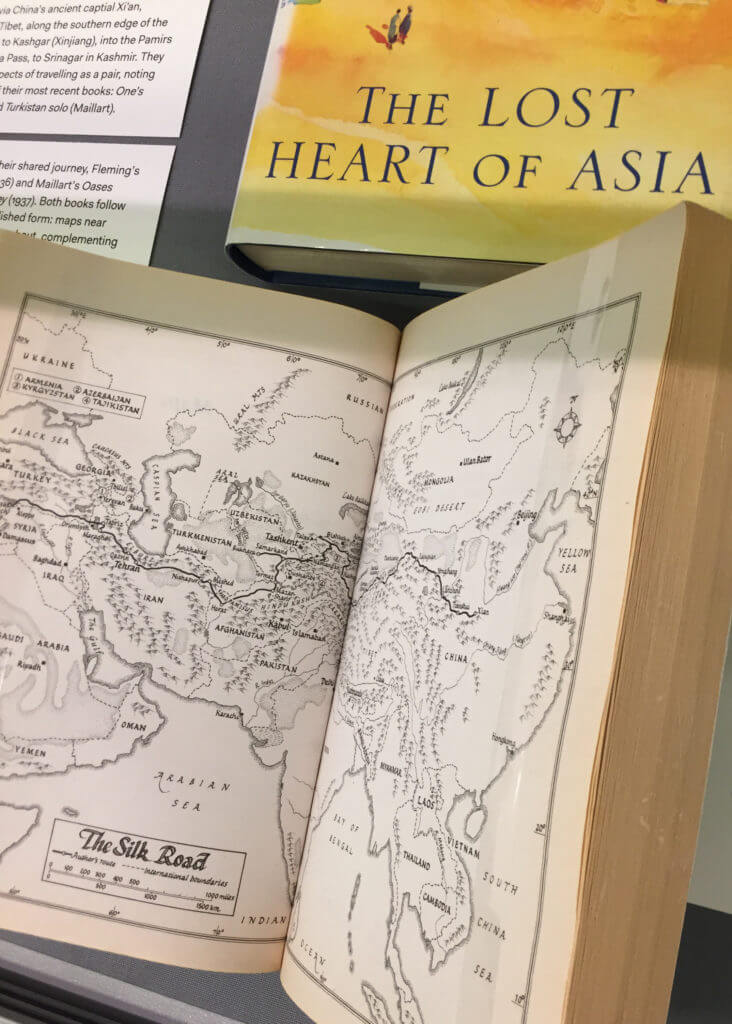

Colin Thubron

The lost heart of Asia (1994)

Shadow of the Silk Road (2006/7)

In the early 1990s, the British travel writer Colin Thubron (b. 1939) flew to Ashkhabad, capital of the newly-independent republic of Turkmenistan. The recent collapse of the Soviet Union, which set free its Central Asian republics, brought about new access to previously difficult to reach parts of the communist empire. Thubron’s travels in the region took him onward to Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kirghizstan and Kazakhstan. The title of the book that resulted, The lost heart of Asia, is an elegiac echo of Younghusband’s from a century earlier. As published, it distils a literary essence accompanied by just two simple maps and no photographs.

In the early 2000s, Thubron returned to Central Asia, this time setting out from Xi’an for a journey of some 4000 miles whose terminus would be Antakya (Antioch), in Turkey. His route partly followed that taken by Fleming and Maillart, before turning into Kirghizstan and then through parts of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan and Iran. Along the way he revisited friends made in the 1990s to discover how their lives, and the fortunes and national narratives of their countries, had changed.

Thubron’s book of his second journey, Shadow of the Silk Road, appears (materially) modest when compared to his earlier book and those of his predecessors. While true in many respects, the paperback edition of Shadow of the Silk Road is nevertheless graced by four maps showing his route in three sectors, and overall. Drawn by the British book cartographer Reginald Piggott (b. 1930, d. c. 2014), the maps display the graphic clarity and elegance for which he was known. They are labelled in an accomplished italic hand, a clue to Piggott’s earlier efforts to improve handwriting in Britain in the 1950s.

Colin Thubron, The lost heart of Asia

First edition, London: William Heinemann, 1994, 367 pp. + prelims and index. With two maps (uncredited).

Colin Thubron, Shadow of the Silk Road

Paperback edition, London: Vintage, 2007, 344 pp. + prelims, timeline and index. (First edition, London: Chatto & Windus, 2006). With four maps (drawn by Reginald Piggott).